The Christian Temple is an expression and visualization of the presence of the Lord in the material world. The temple is «the House of the Lord because there, the Lord is worshiped, his Word is announced by sermon, and the main sacrament of his Presence, the Holy Eucharist, takes place.

It is the place where the liturgical synaxis of the true believers takes place, which is the visible expression of the body of the Church, the head of which is Christ.

The sacrament of Holy Worship is reflected upon the churches’ liturgics, architecture and iconography.

However, regarding the architecture, and especially the iconography, soon the need to provide answers to the following paradox came up: how is it possible to use drawings and colors to depict not the nature, the individuality or the decay, but the hypostasis of people and things [Saint Theodoros Stouditis: It is not the nature, but the hypostasis of the person portrayed that is shown forth in the icon («Παντός εικονιζομένου ούχ ή φύσις, άλλη υπόστασις εικονίζεται)]. How, in other words, will they be transformed into a revelation of the salvation event? Is it possible a way of existence, which phases out autonomy, space and time as a sequence of the previous and posterior, to be depicted with the material means of the artistic creation?

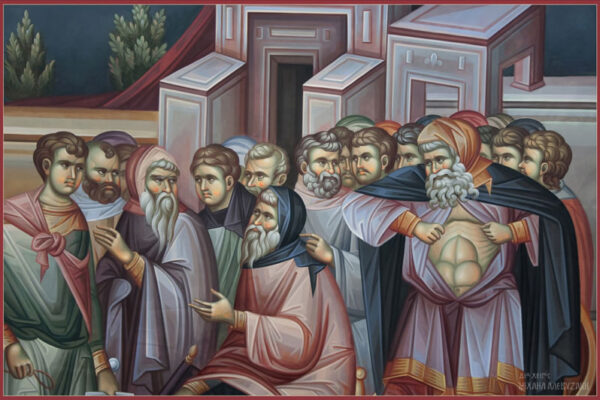

This extreme is achieved via the magnificent expressive force of Byzantine icon, which elevates and transforms the natural reality into a higher conception of form and leads from the way of pretence to the way of truth.

The Christian art expresses the salvation event as it historically happened. It expresses not the individual emotions but the collective acceptance of the «impenetrable mystery which is ministered during the Worship.

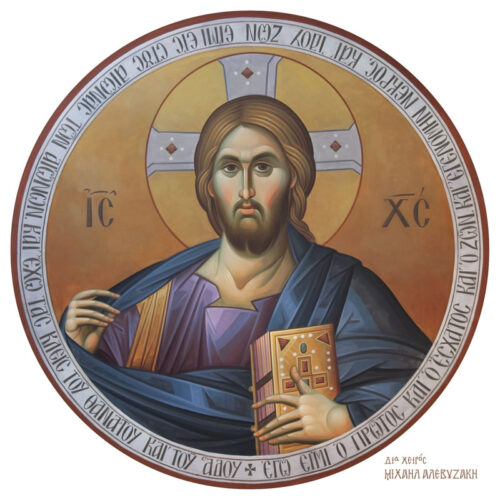

The icon invites for a direct communion/relation with the images, for a transition to the primeval prototype; that is the hypostasis of the iconographically represented person [Saint Basil the Great: For any honor paid to the icon (or picture) redounds upon the original, and whoever bows down in adoration before the icon, is at the same time bowing down in adoration to the substance (or hypostasis) of the one therein painted ( Η της εικόνος τιμή επί το πρωτότυπον διαβαίνει και ο προσκυνών την εικόνα προσκυνεί έν αύτη τού έγγραφομένου τήν υπόστασιν)]. To portray a person according to his hypostasis means to use the artistic creation language to present the divinized human nature.

Saint’s faces are historical but at the same time they manifest the presence of Lord’s glory, according to Apostle Paul (2 Cor. 3:18). The icon depicts the eschatological existence of the person represented; it expresses the bliss of the renewed man in Christ.

The objective rules on how to make an icon subdue the individual perception, the idea, to a view which is an event of communion. The «work of art» is not taken as an individual creation but as a meeting place of the Church with the Eternal God.

For the Byzantines, it is the Church that «paints the icons «by the hand of the painter, who subdues the individual perception to a given iconographical type. It is written in the decisions of the 7th Ecumenical Council that: «The making of icons is not an invention of painters but an approved institution and tradition of the Catholic Church… (Ού ζωγράφων εφεύρεσις ή τών εικόνων ποίησις, αλλά τις καθολικής εκκλησίας έγκριτος θεσμοθεσία και παράδοσις……).

As a consequence, there is a given iconographical type, which, however, does not limit but rather frees the painter from his individual impulses and, as a result, the Church recognizes her truth inside this work of art. This does not mean that the artistic genius of the great Byzantine masters (Manuel Panselinos, Michael Astrapas, Theofanis the Cretan etc.) is abolished, but the icon is not just an artistic suggestion, an individual achievement… it is mainly a revelation, a common attitude in life.

The Byzantine art conveys to the true believer the spiritual truths via the senses: the light and the colour are used in awareness of their impact. The Byzantines believed that both of them are directly associated to God: God is the Source of light. The light being dispersed through the wall paintings symbolizes the primeval, supernatural light, whose source is God, the only source of every light. The Byzantines considered vision to be the highest of the five senses, while at the same time they considered colour and not shape to be the main distinctive characteristic of an object.

The colour perception of the world has a deep importance: the composition of colours and forms ends up in a completely different rhythm, in a rhythm which, as basic it may be in art and perhaps in life, cannot be easily rationalized.

As a result, the painters’ main task was and still is to find those colours that correspond better to the primeval beauty. According to them, the artistic procedure and its work could be considered as imitation. Imitation is called the attempt to transfer the primeval prototype into an authentic repetition, preserving and rendering its meaning from the past till the present. It is clear that we do not talk about servile reproduction, restoration or formalism. Significant variations of the form, composition or colour were and are acceptable within certain limits. But the theological quest for truth applies equally to the Church’s writings and its painting, which is the reason why we have above mentioned the freedom from individual impulse. As a consequence, the obligation to follow a certain archetype comes. The morphological characteristics of the archetypes form a visual rule of the Church within which it is difficult to alter anything.

By referring to archetypes, the Byzantine art is inevitably dominated by the principle of repetition. In this view, repetition is a structural need. The imitation of older prototypes, once a certainty, gradually became an aesthetic problem, as it started to be influenced by the principles of Western art tradition, which compel the artist to originality as well as to constant variation, ending up to present only individual natures. This stance results in a deviation from older works of art.

Today, thanks to the great master Fotis Kontoglou, a renaissance of church art has taken place; a conscious approach of the old prototypes is attempted both in terms of iconographic types and of artistic style. It is essential that the Byzantine icon is safeguarded not as an object of museum value but rather as an anchor that brings man to involvement in the bosom of the Lord, as an expression of Church’s certainty for the constant presence of the «already accomplished. The testimony and the experience of a communion of the living and the dead is the preservation of a memory supporting a tradition, the established practice of a timeless collective experience.

Such a goal requires respect; but respect requires, in its turn, acquaintance, acceptance and knowledge.

Nothing is preserved without certified knowledge; nothing is kept without love; love is the one that keeps everything together; the pursuit is a need steaming from an already expressed demand: the demand that wants Byzantine tradition to be everyone’s legacy. It is not yours what you do not know while you cannot share what is not yours.

The value of the tradition lies not as much in the antiquity that elevates it, but in the trial it undergoes, which in the end determines what is bequeathed from generation to generation. The work of the great Byzantine Christian artists has created a timeless relation with each one of us, because it serves something they knew that surpassed them, it serves community over individuality, the Church over autonomy. This created relation lies at the antipodes of usage, appropriation and self-interest.

This relation presupposes the resignation from ourselves, the self-transcendence, and this is why it succeeds to defeat even time.

Michael Alevyzakis

Athens, January 2012